Blog

2019.07.10

Kanda

Using up your whole bonus? Kitanorimono-chō and the Edokko

Kanda – the city of artisans. Although the names of many streets here are directly tied to the occupations of such craftsmen, what exactly does the name of the spot where Transeuro is located, known as Kitanorimono-chō, mean? The word Norimono, meaning “vehicle” in Japanese, begs the question: Exactly what kind of vehicle is the name referring to? According to one theory, it refers to a kago, which was a palanquin used for carrying the likes of the wealthy, or those of high social status during the Edo era. Others claim it is the mikoshi, which is a portable shrine carried by multiple people used to transport a deity during festivals. Notably, people do not ride on it.

For the people? For the gods? Who exactly was this “vehicle” for?

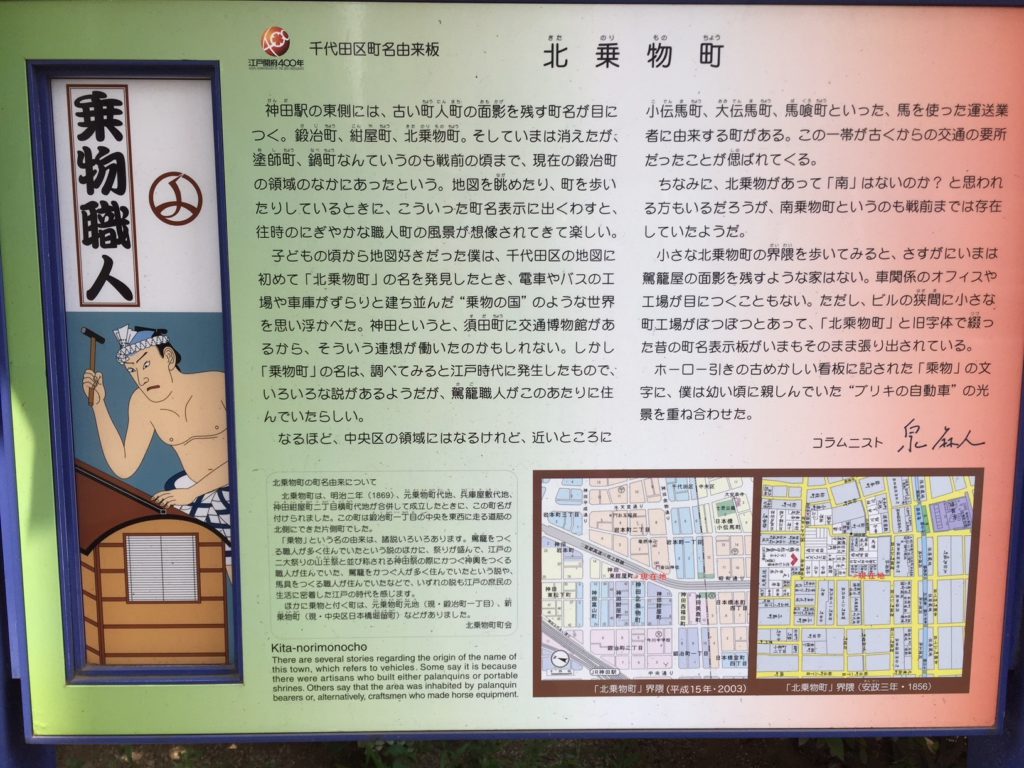

A signboard explaining the origins of the name Kitanorimono-chō

Having no money beyond the evening

According to a signboard built by Chiyoda Ward which details the origin of the town’s name, it seems the people who lived in Kitanorimono-chō were craftsmen who made kago. There is a saying which expresses the spirit of the Edoite artisans of the day: “Money should not be kept overnight”. This simply means that all money earned should be used up before the day ends. In other words, one shouldn’t cling to money, one ought to spend money generously, or put bluntly: you shouldn’t save money.

Do you find yourself thinking this is an extremely short-sighted and reckless way of living? Or does it perhaps sound alluring?

A reproduction of the last nagaya of the Edo Era (Fukagawa Edo Museum)

How exactly were they able to survive that way?

Looking at the payment system of craftsmen of the time, we find that most of them were live-in workers in their masters’ premises until they grew skilled enough to stand on their own feet. In those days the concept of minimum wage didn’t exist, so they earned practically no money for their work as apprentices. However, their food, housing, and sometimes clothing were taken care of – although they hardly lived in luxury. In such situations, it was impossible to have savings or “keep money overnight”. After becoming independent, they were still paid on a daily basis, so even if they used up the day’s earnings, they wouldn’t have to worry so long as they could work again the next day. Additionally, in some cases they were allowed to have their own house when their skills developed to the point that they could earn money independently. However, a house for a common person in Edo meant a nagaya, not a detached house – those were reserved for daimyos (powerful feudal lords) or the very wealthy. The nagaya were longhouses with tenement-like living quarters lined up in a row inside. There was only a thin wall separating neighbors. Residents in a nagaya were like one large family. Helping each other or sharing food was a matter of course, and it is said some nagaya had only one kitchen out of fear of fires. It is also said that people living in a nagaya shared a sense that the belongings of one person were the belongings of all. Under such circumstances, if you should catch a cold and become unable to work, it’s only natural that others would lend you a helping hand, isn’t it?

Edo – when everyday life was crowdfunded

Fires and the Edo era are so often associated with each other that the terms might as well be synonymous. Imagine how meaningless it would be to amass great amounts of wealth, only to have it all go up in flames. This doesn’t mean, however, that the people of Edo simply chose to live in the moment and go on extravagant spending sprees. As we mentioned regarding the nagaya, the Edo era saw mutual assistance within social groups develop significantly. It seems that it was the type of society where, so long as you were alive, everything would work itself out in the end.

The prototype for modern crowdfunding was already in place. People would form small-scale communities, save up money, and use it for special occasions (such as times of celebration, mourning, and festivals). Although they stood to lose a great deal in the event of a fire, it seems that the people of the Edo era lived their lives not by being overly attached to money, but by placing importance on those around them.

Similar Posts

[jetpack-related-posts]

Leave a Reply